Bill Morrison, cineasta com obras já presentes em edições anteriores do Indie Lisboa, regressa este ano à Competição Internacional de Curtas com Incident. Morrison é conhecido pela sua abordagem arquivística ao documentário e ao trabalho de vídeo. Embora a sua filmografia se situe em várias épocas e explore vários temas, o cineasta é normalmente associado à utilização de gravações antigas e arquivadas em película. No entanto, este já trabalhou diversas vezes com material que não se restringe a arquivos cinematográficos, tendo até chegado a focar-se em captações contemporâneas. Incident insere-se firmemente nesta segunda vertente da sua obra.

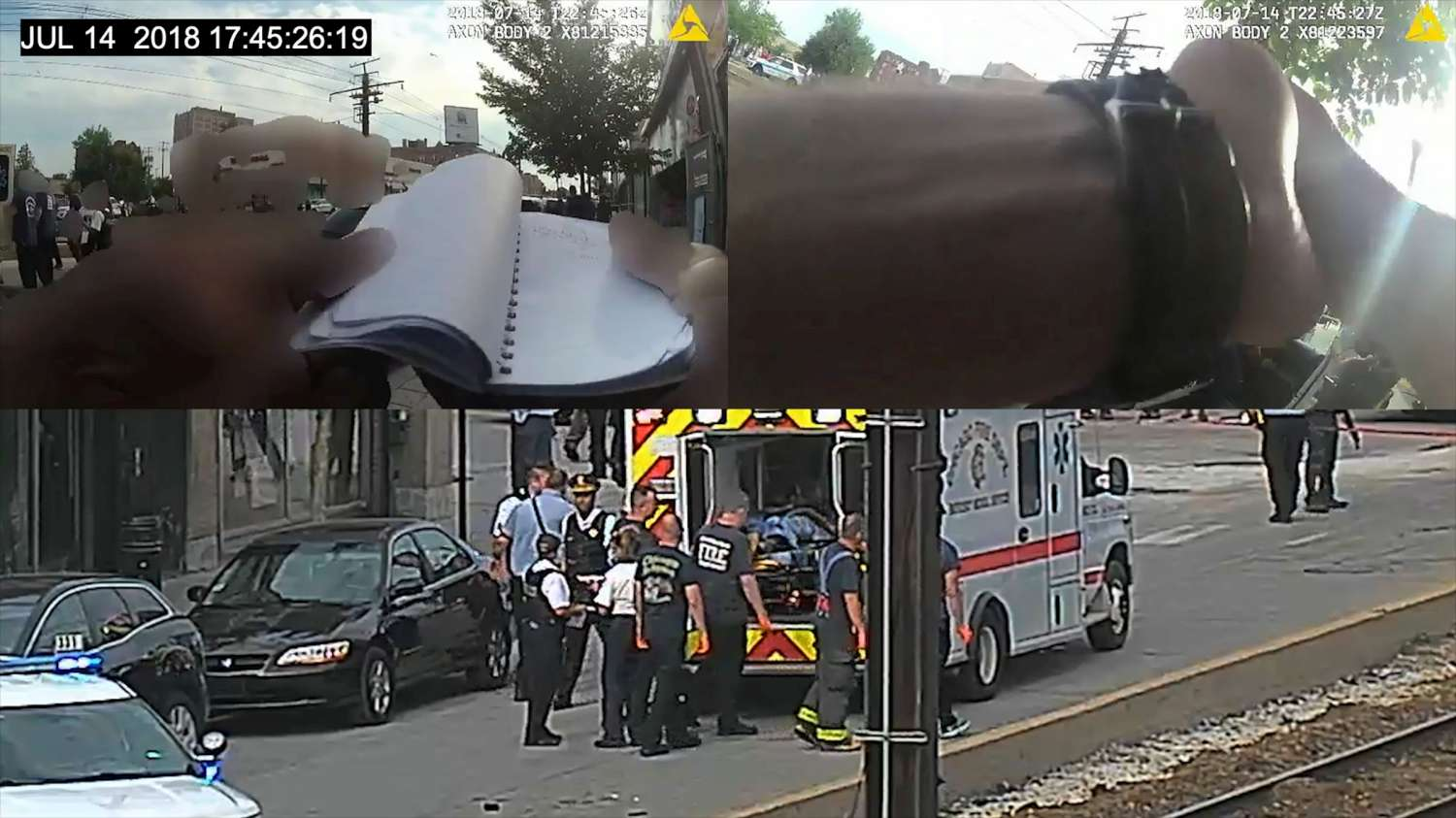

O filme em causa, a partir de uma montagem criativa de vídeo de várias origens (câmaras de segurança, câmaras de polícia…), tenta esmiuçar todos os ângulos de um tiroteio que ocorreu em Chicago de forma a chegar a alguma conclusão. O caso trata-se de um barbeiro de meia idade em posse (legal) de uma arma, que, ao ser abordado sem razão por um grupo de polícias, acaba por ser injustamente morto.

Incident coloca em causa questões sociais óbvias pelo seu tema, mas vai muito além disso. No seu decorrer, esta curta metragem torna-se numa exploração do conceito de vídeo em si e a sua pluralidade, o papel observacional da câmara e a materialidade do vídeo digital.

Entrevista a Bill Morrison no IndieLisboa

Vasco Muralha (VM) — So a lot of your previous work, before Incident, had a big focus on old archival film footage and I wanted to ask mainly how was this shift from that type of archival footage to a new type of archival footage?

Bastante do seu trabalho anterior a Incident focava-se em imagens de arquivo antigas. Como é que se deu esta transição para um novo meio de filme de arquivo?

Bill Morrison (BM) — That’s true, a lot of my footage has not only been archival footage but very old archival footage and so a lot of what has been the point of the earlier stuff is that it shows material degradation, which is, of course, a specific subsection of archival footage. So in this shift to using a contemporary archive, I didn’t feel like I was dealing with film, I didn’t feel like it needed to be edited in the way in which you would edit film. So I was more at liberty to use some vídeo devices, like the split-screens and the quad-screens and the wipes, this kind of thing that I wouldn’t normally use. In a way, the form reflected the type of media that I was working with.

É verdade, muito do meu trabalho tem tratado de filmagens de arquivo muito antigas, cujo objectivo é mostrar a degradação material, que é uma subsecção das filmagens de arquivo. Na transição para um arquivo contemporâneo, não senti que estava a lidar com película, por isso não montei do mesmo modo que monto filmes. Por isso, tomei mais liberdade para usar dispositivos de vídeo, como os split-screens, os quad-screens ou os wipes, o tipo de coisas que normalmente não uso. De certo modo, a forma refletiu-se no tipo de media com que estava a trabalhar.

VM — There is of course a material difference between the old footage and the new footage, but how did you approach it, not in a material sense but in a more contextual sense? How did you feel like approaching footage that was very old with footage from our contemporary types?

Claro que há uma diferença material entre as filmagens antigas e as novas. De que modo abordou, não no sentido material, mas no contextual, estas diferenças?

BM — My choice of older footage always has been a reflection through the prism of contemporary times, usually they’re meant to show how little things have changed, the differences between our society now and hundred years ago. In this case, we’re seeing the systemic racism of the police force in the United States, which is something I have referenced in earlier work, for example Buried News from a few years ago, where I used race riots from a 100 years ago. I think eventually these two films will be shown together.

A minha escolha em filmagens antigas sempre se refletiu através de um prisma contemporâneo. Normalmente é suposto mostrar quão pouco as coisas mudaram, as diferenças entre a nossa sociedade agora e há 100 anos. Neste caso, estamos a ver o racismo sistémico da polícia dos Estados Unidos, que é algo que já referenciei em trabalhos anteriores, como, por exemplo, no Buried News, de há uns anos, onde usei motins raciais de há 100 anos atrás. Acho que eventualmente esses dois filmes serão exibidos juntos.

VM — So do you think there was a certain difference in approaching this topic that is so inherently political, in a contemporary sense, with your already political work in another area? Or do you think it was a more natural shift?

Então, acha que há uma certa diferença ao abordar este tópico tão inerentemente político, num sentido contemporâneo, com o seu trabalho político de outros modos? Ou acha que a mudança foi mais natural?

BM — To me, it felt natural because when I was presented with this archive I saw the potential of the film there almost immediately and I’m always inspired by an archive to make a new film. I’m seldom picking through an archive to support a theory, usually it comes from the archive and my projects grow organically out of that. That was the case here too, the issue of gun control obviously is in a crisis situation right now in the United States, there’s probably a mass shooting that happened today that I don’t know about yet. It’s just preposterous. In some ways, in very explicit ways, this film underscored the hypocrisy of those who are allowed to carry guns and those who are allowed to carry guns but are deemed by the police that they shouldn’t be.

Para mim foi natural, porque, quando me apresentaram o arquivo, percebi imediatamente o potencial do filme e sou sempre inspirado pelo arquivo a fazer um novo filme. Raramente examino um arquivo para apoiar uma teoria, normalmente os projectos crescem organicamente do arquivo. Esse também foi o caso aqui, o controlo de armas está obviamente numa situação de crise nos Estados Unidos. Neste momento, há provavelmente um tiroteio em massa que aconteceu hoje e eu ainda não sei, é absurdo. De muitas maneiras, de formas muito explícitas, este filme sublinha a hipocrisia dos que são permitidos ter porte de arma e dos que são permitidos, mas a polícia considera que não deveriam.

VM — There’s the big use of angles and split-screens as you’ve mentioned and we can piece apart a narrative from all these different views, angles and aspects. In your older work there’s a big focus on the decay of it being old footage, like in Decasia for example, and in the old archival footage having a material/ physical space, but there’s an interesting thing even if its connected to narrative, the zoom ins, split-screens and the lower quality of how it is filmed. There’s also an apparent plasticity of the limits of digital, the pixelisation. What do you think about that?

Neste filme utilizam-se várias câmeras, em diferentes ângulos, os split-screens como já mencionou. Neste sentido, podemos juntar uma narrativa a partir desses diferentes bocados. No seu trabalho anterior há um foco na deterioração de imagens de arquivo antigas, por exemplo o Decasia, em ter um material/espaço físico. Também se pode notar esta aparente plasticidade no caso dos limites do digital, da pixelisação, juntando aos zoom-ins, split-screens e a pior qualidade de como é filmado. Nota-se algo interessante ligado à narrativa. O que pensa sobre isso?

BM — I don’t think of it as a materiality but I do think of it as self-referential. A big part of this film is, of course, the law that I set up in the beginning as a contextualisation and now all of this footage is mandated to be released to the public. That wasn’t the case before, and so this is in ways a police force that is coming to grips with this new law. There’s a performative aspect of it, which they know they’re on camera and they know that anything they say can be used to incriminate themselves, or one of they’re colleagues. So there’s this dance that happens about evening knowledge and the truth of what they saw and how slippery the truth can be, even more when it’s recorded. And so there’s several different types of cameras that were used in this, there’s the establishing shot which is the POD, or Police Observation Device, then we cut to the closed circuit tv, the private security cameras which are the highest resolution that we have and from there we go in to the dashboard cam, and the body-worn cam and its not until we get to the body-worn cam that we have audio. This difference between these silent cameras that establish the scene and the context and we dip into the contemporaneous footage, which gives us the story, then as soon as those cameras are turned off, the ones with microphones, we’re back out in a scene were we have no context or no grasp of what’s happening. That also underlies how little we can possible know, its really dependent of what’s captured at the time and what’s released. Absurdly all of these cameras are manually triggered, which doesn’t serve anyone’s purpose, of course from the police officer it can’t be expected if things get really heated in the moment to say “ohh I have to turn my camera on”, they have other concerns going on. Us, as a public, want to make sure of everything, before it gets heated, what were these circumstances, what was built up, so these cameras should be on all the time.

Não penso nisso como uma materialidade, penso enquanto algo auto-referencial. Uma grande parte deste filme tem que ver com a lei que coloquei no início como contexto, de como agora aquelas imagens tem que ser libertas para o público, o que não era o caso antes. De certo modo, isto é uma força policial que se está a confrontar com esta nova lei. Há um aspecto performativo, eles sabem que estão a ser filmados e sabem que tudo o que dizem pode ser usado para os incriminar a eles, ou a um dos colegas. Há esta dança que acontece sobre equilibrar o conhecimento e a verdade do que viram, e de quão escorregadia pode ser essa verdade, ainda mais quando filmada. Há diferentes tipos de câmaras usadas: o plano geral (establishing-shot) que é o POD, ou Dispositivo Policial de Observação, depois cortamos para o circuito de TV fechada, câmaras de segurança privadas, que são as com maior resolução, daí vamos para a câmara do tablier e depois para as câmeras dos uniformes e só nessas é que temos audio. Então há esta diferença entre as câmaras silenciosas que estabelecem a cena e o contexto, e depois mergulhamos nas imagens contemporâneas, que nos dão a história. Assim que essas câmaras com microfone se desligam, voltamos (para o plano geral) para uma cena onde não temos contexto, onde não conseguimos perceber o que se está a passar. O que também sublinha o quão pouco podemos saber e que está muito dependente do que é filmado na altura e de quando são libertas as imagens. É absurdo, mas todas aquelas câmeras são ligadas manualmente, o que não serve o propósito de ninguém – é claro que não podemos esperar que um polícia, no calor do momento diga “ohhh tenho que ligar a minha câmara”, eles têm outras preocupações. Nós, enquanto público, queremos saber de tudo, antes de ter aquecido, quais foram as circunstâncias, qual foi o crescendo, por isso as câmaras deviam estar sempre ligadas.

VM — As you mentioned before in your work, you used footage of old race riots. That has always been a political approach, but how do you feel about the difference between going from this other footage you use, that has an artist or an aesthetic point in its inception, to this “incidental” one, with utilitarian purpose, where it was filmed for a specific/technical purpose?

Como já mencionou, no seu trabalho usou filmagens de antigos motins raciais. Sempre houve uma abordagem política, mas o que acha da diferença entre ir destas filmagens antigas que usou, que tinham um ponto de concepção artistico ou estético, para este, que é acidental ou utilitário, que foi filmado para um propósito técnico/específico?

BM — In some cases the stuff that’s become artful, as you said, began as utilitarian footage as well, as actuality footage, or a sort of record of something that otherwise would seem. I don’t know if you’d call it artistic, it’s reportage. I guess it’s the treatment of it, as our perspective changes, there are incredible accidents that happen within Incident that I think are artful though I’m not trying to aestheticise a murder, but this seagull is an accident but it becomes the narrator, it brings us into this story and that was of course pretty circumstantial

Em alguns casos, o que se torna artístico, como disseste, começa por ser utilitário. Filmagens de actualidades, uma espécie de registo de algo, não sei se lhe poderíamos chamar artístico, é reportagem. Talvez seja do tratamento que têm, enquanto as nossas perspectivas mudam, há inacreditáveis acidentes que acontecem em Incident, que julgo serem artísticos, embora não esteja a tentar estetizar um homicídio. A gaivota é um acidente, mas ela torna-se no narrador, traz-nos para dentro daquela história e isto foi bastante circunstancial, claro.

Diogo Albarran (DA) – We already talked a little bit about the editing side and multiple cameras that you used to make this film. I was wondering, because a lot of your previous work, the old archive footage, the editing is more about mood, or the meaning with the evolving of those archival images, and here you’re telling a real story. How is this change of approach from working with such abstract material to much more concrete?

Nós já falámos um pouco sobre a montagem, as múltiplas câmaras usadas para fazer este filme. Estava a pensar, muito do seu trabalho anterior, os tais antigos arquivos filmados, a montagem é mais sobre ambientes (mood) ou significados que evoluem com o seguimento das imagens de arquivo, enquanto, neste filme está a contar uma história real. Como é que a abordagem muda, de trabalhar com material tão abstracto para este muito mais concreto?

BM — I just want to clarify that much of my work has not been abstract for a long time now. Dawson City: Frozen Time, for its time was an incredible feat of journalism if I do say so myself. I know that my reputation started with Decasia and people often think of this sort of pure abstraction as a nom de plume, but I just want to draw people’s attention that I’ve been making what you’d call straight documentary films since the minor films, which is 2011, so that’s 12 years. I know that I’m always going to be considered this weird abstract guy. That said, I try to edit in a way which is consistent with the material that I’m using, so with all that stuff that was trapped on film I would use straight cuts, I don’t use dissolves a lot, if I do slow something down it’s in the denominator of 24 frames per second, so I’m either doubling a frame two times or tripling it and not mixing weird frame rates. I don’t use a lot of split-screens of zooms-in, I try to stay true to the integrity of the frame because this was pixels, lower resolution, it was vídeo. I felt like I could treat it in a different way, so that was a different approach. This is a story that took place a couple of miles from where I grew up, a couple of miles from where my mother and sister still live. It’s very much a part of my personal background, this neighborhood, that’s the most marked difference with earlier work, this is in some ways more autobiographical.

Eu gostava de clarificar que há muito tempo que o meu trabalho já não é abstracto. Dawson City: Frozen Time para o seu tempo foi um incrível feito de jornalismo, se o posso dizer. Eu sei que a minha reputação começou com o Decasia e alguns pensam que essa espécie de pura abstração é um nom de plume, mas gostava de chamar à atenção que já faço documentários ditos normais (straight) desde 2011, portanto são 12 anos. Sei que vou ser sempre considerado como um weird abstract guy. Dito isso, eu tento montar de um modo consistente com o material que estou a usar, por isso para tudo o que foi captado em película usei cortes diretos, não uso muito dissolves. Se preciso de abrandar alguma coisa é no denominador de 24 frames por segundo, por isso ou duplico os frames, ou triplico, nunca misturo frame rates esquisitos. Não uso muitos split-screens ou zooms-in, quero manter a integridade do frame. Neste caso eram pixels, baixa resolução, era vídeo, por isso senti que podia tratar o material de maneira diferente, foi uma abordagem diferente. Esta história aconteceu a poucas milhas de onde cresci, a umas milhas de onde a minha mãe e a irmã ainda vivem, isto é parte de meu contexto pessoal, aquele bairro. Essa é a maior diferença para o meu trabalho mais antigo, este é de alguns modos, mais autobiográfico.

DA — I wanted to ask about your stance on documentary filmmaking and truth. In archive analogue films decay plays a major role. Do you see a crisis in documentary filmmaking and truth in this new age of sound manipulation, visual manipulation and a sort of new decay, perhaps in terms of morality or authority, how is that reflected in your movies?

Gostava de saber a sua posiçãosobre a relação entre documentário e verdade. Em filmes analógicos de arquivo, a deterioração tem um papel fundamental. Vê uma crise no documentário e na verdade, nesta nova era de manipulação de som e de imagem e desta nova espécie de deterioração (eventualmente em termos morais ou de autoridade), de que modo se refletem estas questões nos seus filmes?

BM — That’s a great question, I would add to that AI. This is the elephant in the room right now, it’s also when you talk about an AI Image it’s really against the archive. Any film shoot is an archival act, anytime you record anything, what we’re recording now, there’s a timecode, there’s a date-stamp, that makes it archival the moment it happens, it doesn’t need to sit in a box and rot to be archival. It’s immediately archival because it has those numbers and has a title and can be called back again. What AI is doing is stripping those numbers and taking little pieces and decontextualising, deauthorizing, and de-copywriting, through the atomisation of images. The potential, I don’t know if we can imagine it yet, but just what we’ve seen in five years, and the last five months are breathtaking, I guess if I see a change it’s there. When you talk about political actors or manipulation, it can become very difficult very soon to discern what is true and what it’s not, if it isn’t already. Moving forward we’re going to need to see those numbers, and see the timecode as part of any sort of evidence. If we don’t see them, there will be reason to doubt everything.

Ótima questão, eu gostava de acrescentar AI (Inteligência Artificial), o elefante na sala neste momento, quando se fala sobre imagens de AI, que são mesmo contra arquivo. Qualquer coisa filmada é um ato de arquivo, sempre se grava qualquer coisa, estamos a gravar agora, há um timecode, um date stamp, isso faz com que seja arquivo assim que acontece. Não precisa de apodrecer numa caixa para ser arquivo, é imediatamente arquivo porque tem aqueles números, aquele título e pode ser convocado. O que a Inteligência Artificial faz é tirar esse números e pegar em bocadinhos pequeninos e descontextualizar, desautorizar, retirar o copywrite através da atomização da imagem. O potencial não sei se o conseguimos imaginar ainda, mas os últimos 5 meses são de cortar a respiração. Se vir alguma mudança é aí. Quando se fala de actores políticos ou de manipulação, pode ser muito difícil discernir o que é verdade do que não é. Daqui em diante vamos precisar de ver os números, e ver o timecode como parte de qualquer tipo de prova. Se não os virmos, teremos razões para duvidar de tudo, se é que já não temos.

DA — Do you think that having this new movement and this new age beginning, archive movies, whether old ones or new ones, could in a way be a response and serve a counteraction by going to the past and bringing the past to the present or to the future and contextualizing it, could it be a weapon against this manipulation of images?

Acha que neste novo movimento, esta nova era que começa, os filmes de arquivo, quer os antigos ou os novos, podem responder, de certo modo servindo de contra-acção, nesse ir ao passado e trazê-lo para o presente e para o futuro, contextualizando-os? Poderá estar aí a arma contra a manipulação das imagens?

BM — We’ll have to see, obviously you can add a timecode to anything, I added a timecode to Incident, but it doesn’t make it real. We’re going to have to be very clever about how we communicate to each other to say “This actually happened” because we’re already in thin ice. In my country there’s an enormous amount of the population that wants to deny that a presidential election took place, this is an example of a leader of the free world, what does that say for the rest of the world, this could happen on a regular basis, but people just say “that’s not real”. I don’t know if looking back at archival footage will always save us from that, I think our task at hand is to concern what happened, it’s incumbent upon all of us, it’s kind of a scary time we’re entering.

Vamos ter que ver, claro que se pode por um timecode em tudo, eu pus um timecode no Incident, mas isso faz dele real (o timecode). Vamos ter que ser muito espertos na forma como comunicamos uns aos outros para dizer “isto aconteceu”, já estamos em terreno escorregadio. Nos Estados Unidos há uma grande parte da população que quer negar que uma eleição presidencial aconteceu, isto é um exemplo do líder do mundo livre, o que é que isso diz ao resto do mundo? Isto pode acontecer com regularidade, as pessoas simplesmente dizerem “isso não aconteceu”. Não sei se o arquivo nos vai salvar sempre disso, penso que a nossa tarefa agora é discernir o que acontece. É um período perigoso em que entramos.

DA — On that point of a certain objective reality and people denying what the world considers objective reality, I would like to go to your movie and try to get a sense of if you think it’s objective, if you think what’s there is there. Because I imagine, for example, seeing that the police officer got a very short sentence and got out fast, I could imagine those images being misconstrued and seeing a lot that happened we still don’t see enough to be able to bulletproof it and say this is exactly what happened (or how it happened).

Gostava de ir ao filme e tentar perceber se acha que ele é objectivo, se acha que o que lá está, lá está? Imagino as imagens a serem deturpadas (pela polícia), visto que o polícia teve uma sentença leve e saiu rapidamente da prisão. Será que tendo visto tanto, não vimos o suficiente para conseguirmos dizer com certeza “isto é exatamente o que aconteceu?”

BM — Just to play devil’s advocate, and devil, in this case, being the officer who shot the 37-year-old barber walking back from work on a Saturday night. Those are very rough streets and you can’t show weakness, with a different character this could’ve turned out differently. In defense of the police, they do have to make split-second decisions, in this case, they created the situation where they had to make that split-second decision, there was no reason this needed to escalate. I also think that footage shows the cop arriving with his hand on his gun, as do two other officers, and he’s ready to go, as soon as the victim goes between the car, he pursues him with the gun, and it’s only then that you see Augustus reach for his gun, in reaction to this cop, he knows he’s going to die anyway, what else can you do? I think it does show that. I do think he got off easy, Augustus didn’t have a family that was in support of him, it wasn’t a law case brought by an aggrieved family, he was a loner, and people didn’t know him that well, that weren’t a lot of people lobbying on his behalf. The police thought that the fact that he showed a gun and he might’ve been reaching for it was enough of a grey area that they could run for cover. I think there’s no question in my mind that it objectively shows that they created that situation.

Para ser advogado do diabo, sendo o diabo o agente da polícia que matou o barbeiro de 37 anos que voltava para casa do trabalho num sábado à noite, aquelas ruas são complicadas, não se pode mostrar fraqueza, com um personagem diferente isto podia ter sido diferente. Em defesa da polícia, eles têm que tomar decisões em segundos, neste caso, foram eles que criaram a situação em que precisaram de agir em segundos, não havia razão para escalar a situação. Também acho que as imagens mostram que o polícia aparece com a pistola na mão, tal como dois outros, ele está ready to go – assim que a vítima corre entre os carros, em reação aos polícias, ele persegue-o com a arma e só nesse momento é que se vê Augustus esticar-se para a arma, novamente em reação a este polícia. Ele (Augustus) sabe que vai morrer, que mais podia fazer? Eu acho que mostra isso. Também acho que a polícia se safou. O Augustus não tinha família para o apoiar, isto não foi uma acusação legal de uma família ressentida, ele era solitário e as pessoas não o conheciam muito bem, não havia gente a fazer lobbying por ele. A polícia pensou que o facto de ele mostrar uma arma e talvez estar a tentar alcançá-la seria área cinzenta suficiente para correr para abrigo. Não tenho dúvidas que o filme mostra objectivamente que eles é que criaram aquela situação.

DA — How did you come across this footage?

Como é que encontrou estas filmagens?

BM — A friend of mine named Jamie Kalven, who’s a journalist in Chicago had actually filed a case against the Chicago Police Department to sue for the dashboard cam of the Laquan McDonald case, that happened in 2014. So it was really because of his efforts and another journalist that this law was passed, whereby the Chicago PD had to release the footage. With the Invisible Institute, they collaborated with Forensic Architecture from London and digitally recreated what had been enacted, reenacting those scenes using the existing footage and with that created 6 different vídeos that contextualize this incident in different ways. When Jamie wrote about it he referred to some of the footage in footnotes, which sent me to the archive, and by reviewing all of the footage that was in the archive that had been uploaded by the Chicago Police Department, I started to understand this as a story that could be told in a different way. It was really through Invisible Institute that I became aware of it.

Um amigo meu chamado Jamie Kalven, um jornalista de Chicago, tinha aberto um caso contra o Departamento da Polícia de Chicago, processando-os pelas filmagens do tablier no caso Laquan McDonald, que aconteceu em 2014. Na verdade, foi por causa do esforço dele e de outro jornalista que esta lei foi aprovada, na qual a Polícia de Chicago tem que libertar as filmagens. Em conjunto com o Invisible Institute, colaborámos com a Forensic Architecture de Londres e recriou-se digitalmente o que tinha ocorrido, recriando as cenas usando as filmagens existentes. Com isso fez-se os 6 vídeos que contextualizam este incidente de maneiras diferentes. Quando o Jamie escreveu sobre o que aconteceu, referenciou algumas das filmagens em rodapé, o que me apontou para o arquivo e ao rever as filmagens que estavam no arquivo, carregadas para a internet pela Chigado PD, comecei a perceber que esta história podia ser contada de um modo diferente. Mas foi pelo Invisible Institute que conheci o caso.

Diogo Albarran e Vasco Muralha